On the 15th of September, the eyes of the whole financial market were turned to Ethereum – the second-largest cryptocurrency in the world. The reason behind that was an upgrade called ‘The Merge’. It was part of the ecosystem upgrades aiming to make Ethereum more scalable and energy efficient. To achieve that, the existing execution layer of Ethereum was joined with the Beacon Chain. That enabled the transition from ‘proof-of-work’ consensus to ‘proof-of-stake.’ But let’s start from the beginning.

Ethereum was launched in 2015 and grew on the core concept of Bitcoin – a single, immutable, permissionless decentralized ledger that can be maintained without intermediaries. So far, transactions used to be confirmed by ‘proof-of-work.‘ In PoW, miners work on solving complicated math problems. The fastest of them become the validators. For their work, they are rewarded with freshly minted cryptocurrencies.

The key is that miners need to spend on computers and electricity in order to be rewarded with virtual assets. In distributed ledgers, validators do not need to be trusted authorities. In theory, anyone can confirm transactions. The other users of the ledger trust validators as they have strong incentives to do the right thing. Miners prove their commitment by spending a lot of money on computers and electricity. If they tried to scam, they would risk undermining the value of the crypto, meaning undermining their own investment. Maintaining trust and value of the cryptocurrency is in the best interest of miners (and their wallets).

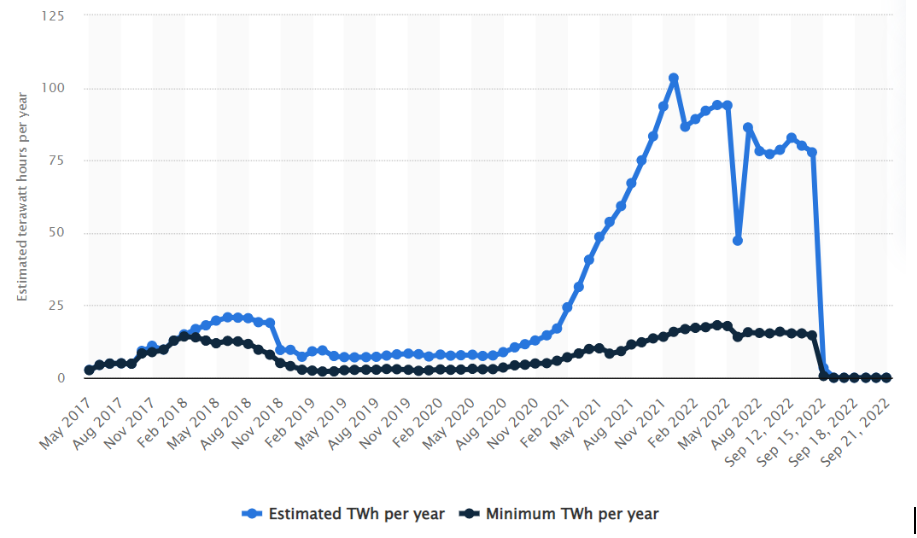

What seemed to be the greatest asset, relying on incentives, established some serious problems. First of all, math problems need to be complex to guarantee the safety of the network. Consequently, solving meaningless math problems wastes loads of energy and emits a lot of carbon. It is estimated that a single ETH transaction consumes the same amount of energy as the average US household in a week. Energy resources also create inefficiencies in economic terms. With rocketing energy costs, validators need to be handsomely rewarded to voluntarily confirm transactions. In the aftermath, high costs cause scalability limitations.

Estimated and minimum energy usage in proof-of-work consensus

Another problematic factor stems from the fact that most crypto mining currently takes place on ‘farms’ – warehouses filled with computers stacked on top of one another to pump out cryptocurrencies. That arouses controversy around the concept of decentralization through public participation. In reality, cost serves as a great obstacle to public participation. Computers are gathered in a few mining pools and create a form of mining centers.

As said at the beginning, ‘The Merge’ integrates the two existing independent chains: the execution layer and the consensus layer (the Beacon Chain). The Beacon Chain was not originally processing the main network transactions. It was reaching a consensus on its own state by agreeing on active validators and their account balances. After extensive testing, it was time for the Beacon Chain to reach a consensus on real-world data. After The Merge, the Beacon Chain became the consensus engine for all network data. It also merged the entire transactional history of Ethereum, so no history has been lost. Mining is no longer the means of producing valid blocks. Instead, the ‘proof-of-stake’ validators have adopted this role and are now responsible for processing the validity of all transactions and proposing blocks.

Proof-of-stake‘ is still a solution aiming to reach a consensus. However, instead of providing computationally intensive proof, participants only need to prove that they have staked coins. This indicates that control over the network is no longer dictated by the amount of energy used, but by the value of ETH one possesses. The more coins a validator stakes, the higher probability that he will be randomly chosen to confirm the block. Validators tie up some of their ether, so they cannot use it as they verify transactions. The staked ether takes over the role of collateral – if the validator behaves dishonestly, his coins will be destroyed.

Responsibilities of a validator include: proposing new blocks, submitting attestation (votes), and monitoring offenses. To become a validator for Ethereum, one will need to stake 32 ether, worth roughly $45,000 as of September 2022. Like miners in ‘proof-of-work,’ validators in PoS are rewarded for taking part in the process. In order to get an ether, they need to attest to a new block, meaning they accept it as accurate and rules compliant. Ethereum’s PoS doles out penalties as well. Penalties are dispensed when a validator proposes a block with a false transaction or false data history, a significant portion of the validator’s staked resources are slashed by the protocol. Further, the validator is banned from the network to punish this bad behavior.

How does PoS addresses the problems arising in PoW? Enthusiasts say that validators finally will not be gathered around a few biggest mining pools. As PoS, Ethereum requires at least 16,384 validators, the network will be more decentralized and, consequently, more secure. As mining is no longer required, Ethereum should also consume 99.9% or so less energy. It’s like Finland has suddenly shut off its power grid, according to one estimate. Reduction in energy consumption leads to diminished rewards for creating a block as it requires less subsidy from the network. Under PoS block reward is nearly 90% lower. Lastly, PoS can be the first step to enable scalability through sharding.

Sharding refers to splitting the entire Ethereum network into multiple portions called ‘shards.’ The idea is to break the main chain into separate segments, where nodes only need to verify a subset of transactions. Each shard would contain its own independent state, meaning a unique set of account balances and smart contracts. In an Ethereum context, sharding can not only reduce network congestion and increase transactions per second, but also offer low transaction fees while leveraging the security of Ethereum.

Nevertheless, ‘Proof-of-stake’ has drawn more than a few critics. Critics believe that “proof-of-stake is fundamentally unable to produce a distributed consensus within Bitcoin’s trust model.” They also argue the system risks leading to more centralization. While blockchain is supposed to not have leaders in charge, critics worry that ‘proof-of-stake’ would unintentionally steer blockchains back in the direction of centralized control, since users who have the most ether have the most power over the system. The four largest validator node operators, Lido, Coinbase, Kraken, and Binance, amass 54% of staking activity. Lido itself controls over 33% of shares. By controlling a significant chunk of staked ether, Lido’s centralization increases the risk of validator slashing, governance attacks, or smart contract exploits.

To conclude, ‘The Merge’ was a huge upgrade with great consequences for the whole industry. In contrast with many proponents that indicate the sustainability of the solution, there are opponents who raise concerns in other areas. ‘The Merge’ was followed by a sharp drop in the price, however, it started rising back after a few days. The market needs more time to unambiguously verify whether the change was needed.

Share this post

Written by

RedCompass Labs

Resources